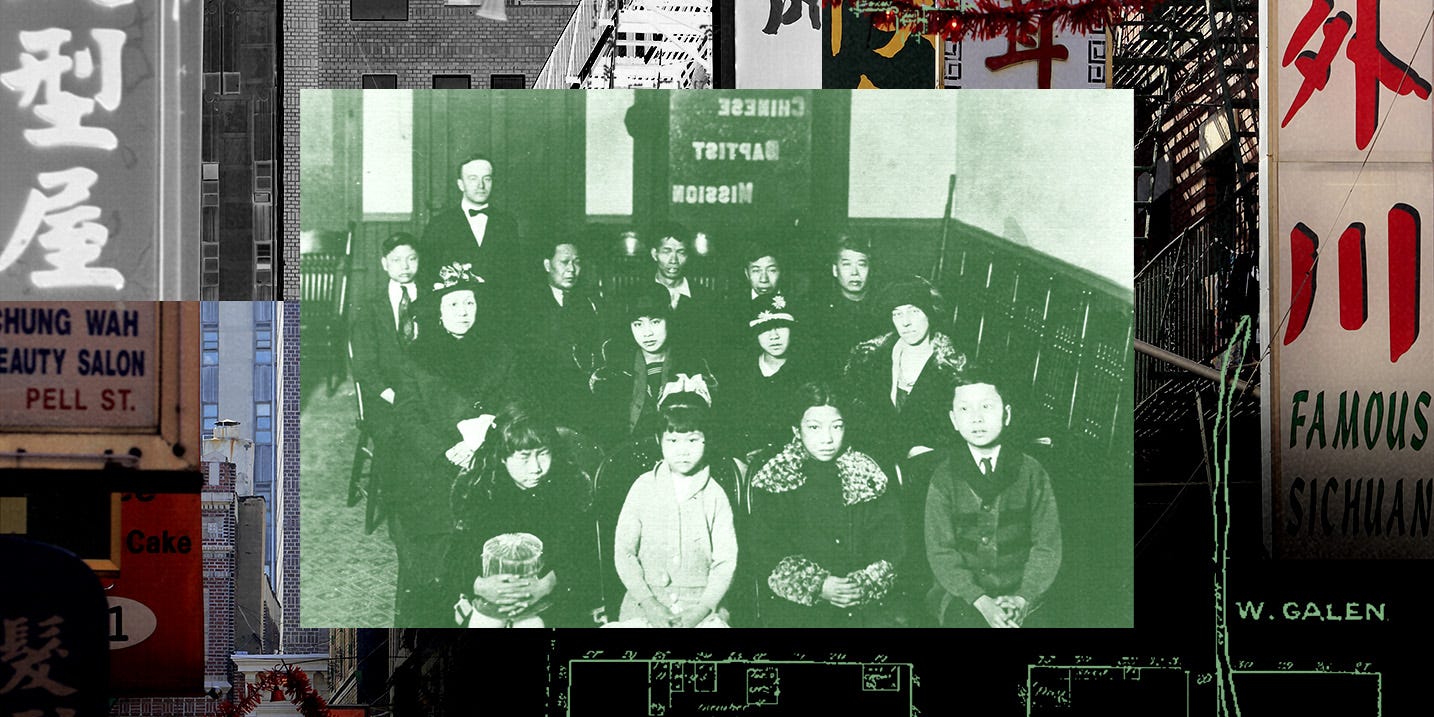

The earliest Chinese immigrants came to the US in the middle of the 19th century, seeking safety from the threat of famine that afflicted drought-stricken China at the time. These eager laborers were attracted to towns all over the West Coast by the promise of the Gold Rush and the railroad building business, originally settling in places like San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Seattle.

Chinese Americans reached their first significant peak in the 1880s, accounting for about.21% of the nation’s population and dispersed from Butte, Montana, to New York City.

From the animosity they encountered in their immediate neighborhoods all the way up to the US federal government, this initial wave of immigrants quickly discovered that they were not welcome in their new homes. The Chinese Exclusion Act, passed by Congress in 1882, forbade the entry of any Chinese laborers. The only immigration limitation against a particular nationality in the history of the nation is still the Chinese Exclusion Act.

The country’s first “Chinatowns,” which are any settlements outside of Asia where the population is predominately Chinese, were created as a result of these discriminatory legislation.

According to Min Zhou, a professor of sociology and Asian American studies at UCLA, “immigrants tended to form their own ethnic enclaves because of the early disadvantages associated with immigrant status.” They were stuck with nowhere to go.

Most notably, the Chinatowns in Manhattan, New York, which is the largest in the nation, and San Francisco, California, which is claimed to be the oldest, are two famous metropolitan Chinatowns that were founded in the 1880s and are still thriving today. However, numerous more Chinatowns perished. Most were either forced to relocate or destroyed by acts of arson . However, during the slowdown of their particular labor industries, like as mining and railroad building, the majority of them faced a natural fall in population. Some of these early Chinatowns have completely disappeared, while others still bear faint traces of their existence, such as a paifang gate that has been abandoned but is still intact or faded Chinese inscriptions on decrepit buildings.

Even though the town’s Chinese American population is declining, successive generations of restaurant and retail owners in Butte, Montana, strive valiantly to uphold their family traditions. A Chinatown that had all but vanished in Detroit, Michigan, is now being put back together by activists and artists. A plain strip mall in Atlanta, Georgia, has evolved into a haven for Asian Americans living in the South. Each Chinatown shows the particular struggles and achievements of being Asian in this country as well as the frequently forgotten histories of America.

However, Montana Beginning with Chin Hin Doon’s arrival in Butte, Montana, in 1875, the Chinn family was among the first Chinese immigrants to make their home there.

People who once called Detroit’s Chinatown home still clearly recall it as a secure gathering place for the neighborhood despite its volatile past. The great-grandson of Joe, Curtis Chin, grew up in the Chung’s back kitchen. “I observed everyone in Detroit pass through our restaurant, including the mayor and old Chinese bachelors as well as pimps and prostitutes. The fact that Chinese restaurants are so well-liked and are among the few places in our country where you can see a cross-section of people, in particular Chinatowns, is, in my opinion, a lovely thing. where we may still connect as a group.”

On May 15, 1963, a parade passes through the Chinatown of Detroit along Cass and Peterboro. Wayne State University and the Detroit News Library Walter P. Reuther show fewer the main street of Detroit’s second Chinatown, which was established in the 1960s but quickly abandoned after a spate of violent murders. Using Annie Fu’s Insider content One of the leaders working to rekindle that sense of connection through various redevelopment projects including Detroit’s Chinatown is Ann Arbor, Michigan-based artist and activist Chien-An Yuan. A cultural night market is one of his main ongoing projects, with the aim of fostering local organization collaboration and offering a regular gathering place for the neighborhood.

Yuan observed that it has proven challenging to agree on plans and manage relationships amongst various organizational stakeholders. A local group’s request for a memorial protest was met with a cease and desist order earlier this year, during the planning stages of the Vincent Chin 40th Remembrance and Rededication , an occasion intended to celebrate Chin’s legacy and fight anti-Asian prejudice. A discussion over the night market involving local community leaders and groups came to a standstill at the beginning of August.

Asian Americans not only in Georgia but also throughout the Southeast now flock to Chinatown Square Mall as their safe refuge. Yaqin Cao, a longstanding resident of Charlotte, North Carolina, has visited Atlanta’s Chinatown on average every two years for the past 20 years. When her favorite Asian markets and eateries in Charlotte shuttered, she first started making the trek. I used to leave between four and five in the morning, travel for about four hours, and arrive home after a full day of eating and shopping by about midnight. Now that so many of her friends are aware of Atlanta’s Chinatown, they frequently travel together in carpools of up to 20 people, filling numerous vehicles, or even hire buses.